Scott

Crawford

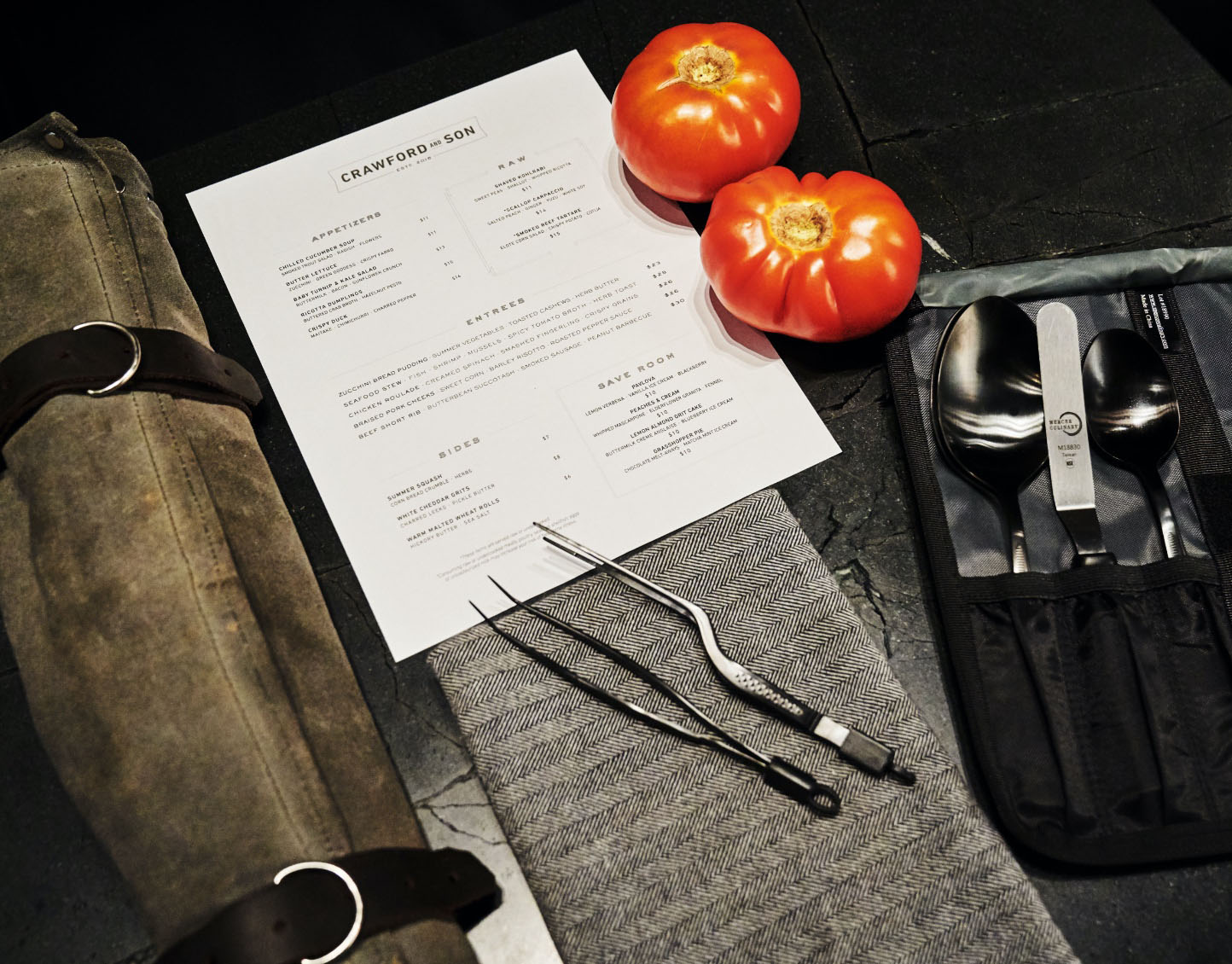

Chef and Owner of Crawford & Son and Jolie in Raleigh, North Carolina

S itting down at the dimly lit restaurant, you’re filled with anticipation. You’ve been trying to get a reservation for weeks and you finally hit. Eight o’clock, Thursday, for two.

Everyone’s been talking about this place and it’s your first time here. The waitress comes back with your cocktails.

“Try the kohlrabi,” she says.

“The what?”

Curious enough to taste something you’ve never heard of, you take a flyer. The plates land. It looks almost too elegant to disturb. You take your first bite.

It’s not weird, just…new. Your head turns to the side as you try to make heads or tails of it. The flavors swirl on your palate, finally settling. The turn becomes a nod. “Whoa, that’s incredible.”

“The Crawford name has been on a farm, a saw mill, a machine shop. Crawford & Son was just me carrying on that tradition.”

Scott Crawford believes in the power of “the full tilt,” as he and his team like to call it. In conceptualizing a dish, he explains this as the finishing touch that elevates it from good to great. As his guests experience these signature dishes, he wants to see it in their body language too. “If someone tilts their head when they’re eating with us, we know we’ve done something right,” he says.

It’s not confusion that he’s after, but a change in perspective. That moment when you encounter an enlightening take on a dish you thought you already knew. Or an “underdog ingredient” that opens your eyes to its depth and potential.

“They call us the vegetable whisperers,” he says. “It’s easy to take a great steak and make it taste good. It’s a little more difficult to take a kohlrabi and have people talking about it days after they’ve experienced it.”

Growing up in rural Pennsylvania, Crawford came to professional cooking almost by accident. “My first job in the food industry was as a busboy. I had no experience,” he says. “It didn’t take long for me to be promoted after that, to a server and then a bartender.”

As fate would have it, one day someone in the kitchen didn’t show. His chef at the time asked him to fill in. “Each thing that they showed me, I tried to do at a high level, with some accuracy, and some integrity. And at the end of the shift, the chef said, ‘You belong in the kitchen.’ And there was really no turning back.”

The kitchen became the perfect setting for him to channel the “manic energy” that he’s always possessed. He arrived in Raleigh, where he’s lived for more than a decade, via Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and California.

Along the way he learned some formative lessons, but Crawford was determined to put in his time before striking out on his own. “I knew that I was operating on ego as a younger chef,” he says. “I wanted to wait until I no longer had something to prove to myself, when I knew that I was established enough to operate, to try to do the right things for the right reasons. I feel fortunate that I waited because I actually had the maturity to make a profitable business, as well as a creative outlet.”

Eating at Crawford & Son and Jolie, you’ll recognize both Scott’s deep knowledge of traditional cuisine and technique and his willingness to cast them off when it’s time to try something new. His food is sophisticated and complex, with familiar flavors throughout that keep every dish grounded.

He explains his cooking inspirations, like most things, with clarity and humility. “There’s who, and there’s what for inspiration for me,” Crawford says. “The who would be the people I try to surround myself with—the smartest, most creative people I can. Often younger than me, with fresh ideas. Collaborative work is always better. The what? That’s the products, the seasonal produce, the different breeds of animals.”

Raleigh is home to North Carolina’s state farmer’s market, a sprawling 75-acre complex that showcases the region’s diverse agriculture. Produce and meat from local farms feature prominently on his menus.

“You can’t possibly craft a great dish without great ingredients,” he says. “My relationships with the people who supply my restaurants are long-term. They understand my standards, my demands, and I understand what it’s like for them. We’re not just committed to buying their product. We’re committed to helping them run a successful farm.”

At the core of his identity and his practice as a chef is craft.

“Craft means to me, quality, integrity, time and care,” he says. “I grew up surrounded by craftsmen. The Crawford name has been on a farm, a saw mill, a machine shop. Crawford & Son was just me carrying on that tradition.”

In regards to mastering his own craft, he believes that eventually you reach the point where “you can start to taste things in your mind.” To manifest these imagined flavors, you have to nail the fundamentals. “First and foremost [are] knife skills. We use knives as an extension of our hands,” he says.

Allowing these hands to express his ideas comes from practice beyond the kitchen too. “Music affects my creative process,” Crawford says. “We have these ideas in our head, but getting them from our head to our hands can be challenging. With guitar playing, it’s a way to allow those creative ideas to flow through my hands.”

Crawford is ready to take risks, but only measured ones. His restaurants on North Person Street in downtown Raleigh are pillars of the adjacent Oakwood neighborhood. “I’m crafting for my community,” he says. “Raleigh is growing. With that growth, I’ve seen a willingness to try new things. I have established a trust with my community. They will agree to try new things and I’ll deliver in a way that I know they’ll enjoy.”

There is clearly much more to come in the Crawford world, and although they’re abundant, the awards and accolades that have followed him throughout his career never come up once during the conversation.

“I would like my legacy to be pretty simple,” he says. “Did I create lasting memories for my community? Was I a good leader for my people? Did I do a good job as a father and a husband? Did I practice my craft at the highest level I could? If I could answer those questions, ‘Yes,’ that’s what I would love for my legacy to be.”

He’s confident in his desire to succeed on his own terms.

“We have these ideas in our head, but getting them from our head to our hands can be challenging.”