Lee

Wybranski

Artist for the Icons of Golf

A golf course is a vast place, full of angles and undulations, ebbs and flows. Through the duration of a round, following your ball across the grass brings new vantage points with every shot. And today’s view is always different from tomorrow’s.

Over time, certain areas begin to stand out. That fairway bunker that might appear innocuous is a catalyst for story after story of heroics and hilarity. A par-four that comes across as straightforward becomes the favorite hole for its strategy and subtlety. Sweeping vistas always have their place, but sometimes the seemingly everyday is the most emblematic.

Lee Wybranski, perhaps golf’s most notable artist, is frequently tasked with sifting through everything that makes a course unique and settling on a single snapshot that captures its defining character. For regulars and members, it may take years to find that singular place at their home course. Wybranski is challenged to do so during a few days of scouting.

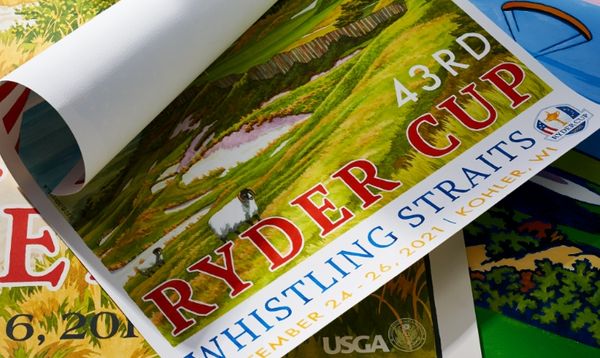

You may not recognize Wybranski’s name, but if you follow the game at all, you’ve likely encountered his body of work. While his company is well-versed in all things golf, from designing club logos to scorecards and beyond, he’s largely associated with the posters he creates every year for each of golf’s major championships. His style is influenced by both classic landscape paintings and vintage travel advertising. The posters themselves respect tradition, while maintaining a playful whimsy and clear presentation.

We linked up with Lee as he was doing his scouting work at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, home of the 2022 U.S. Open Championship. For his major championship poster work, he typically visits the host course about a year out from the tournament.

“I’m not trying to photo-represent the course so it feels like you could walk into the painting, but I am trying to evoke a feeling or stir a sensation in the viewer that makes them want to be part of the event.”

Wybranski’s excitement about the project with the club is both obvious and understandable. An enthusiastic student of golf history, he is transfixed as he absorbs the vistas and the spirit of one of the true treasures of American golf. His movements are sharp and purposeful, constantly scanning the scenery for landmarks and distinct features. Hauling a giant ladder across the course, this is a man who will stop at nothing to find the right view.

“These days, I’m fortunate to work for the type of clients that I was only dreaming about 10 or 15 years ago,” he says. “Working at The Country Club is about as close to the top of the mountain as you can get. Whenever a championship goes to a historically significant, classic venue that it hasn’t been to for decades, it’s a magical moment, and to be tasked with rendering that moment in pictorial form is just about as fun as my job gets.”

Art has been a great passion since he was a child. He was always the kid in the back of the class drawing, and the comic books that captivated 10-year-old Lee still influence the way he seeks out drama in his paintings today. But Wybranski found his way to golf more as a happy accident rather than a natural progression. His connection to the game came mainly through his work. Determined to succeed as an artist following his college years, he earned a living executing architectural drawings in pen and ink.

Recognizing that established golf clubs with iconic clubhouses might be receptive to his architectural renderings, he approached several in metropolitan New York to gauge their interest. And he got off to a pretty auspicious start.

“Winged Foot was my first commission in the game,” he says. “Saucon Valley was my second, and within a few months I had evolved into a golf artist. I just had an artistic inclination and a lot of hustle.”

Despite growing up a few miles from the historic Merion Golf Club, his relationship with the sport during his early life was almost entirely tangential.

“It wasn’t until after I began working in and around the game that it occurred to me that I should try it out and see if I liked it,” he says. “At the very least, it would clearly inform my work, and I would have more of an understanding of the subtleties. So I gave it a swing, so to speak, and got bit with the bug like everybody does. I love it.”

Given the fluency with which he speaks to everyone at TCC, it’s hard to believe that he only came to the sport later in life, but it’s clear that golf is now both a passion and a profession.

Genuine and warm, Wybranski has a wide-eyed fascination with the world around him and the people he meets. After traversing the course with him, watching his mind at work, your own attention to the nuances of your surroundings becomes sharper, too.

Wybranski does not set out to merely create a beautiful work of art. Through the selected typeface, chosen scenes and subtle details, his posters become the calling card for the tournament and occasionally even predict the setting of its iconic moment. While he’s always seeking to accurately convey a sense of history where it’s notable, the paintings themselves are not bound by strict realism, nor should they be.

“I’m not trying to capture every blade of grass out there,” he says. “I’m not trying to photo-represent the course so it feels like you could walk into the painting, but I am trying to evoke a feeling or stir a sensation in the viewer that makes them want to be part of the event.”

Sometimes that means subtly shifting a few trees around, framing the view with a strategic addition or blending a color that is different from its exact physical expression.

“I mix all of my greens from different blues and yellows and various other colors—sort of dirty them up to give it a little bit of richness and an unexpected feel,” he says.

And even if each of his posters has a unique point of view, the design guidelines Wybranski follows are largely consistent. He’s often working like a casting director.

“When I embark on a project, I seek to identify three or at most four characters in the play,” he notes. “There’s one main character, maybe two, and then one or two supporting characters. I feel like this is partly what makes the work have the iconic feel that it does, by including only what’s important and none of what isn’t.”

Wybranski the artist needs Wybranski the businessman. He’s not jaded, just mindful that his art, especially his poster art, is ultimately a commercial product. It’s his ability to maintain his love of art without becoming too precious about his own that keeps him personally fulfilled. It also keeps his clients coming back.

Wybranski is rightfully proud of the way that his art resonates with the broader golf community. Because he’s frequently attending tournaments and actually meeting many of the fans who are purchasing his posters, he gets plenty of real-time feedback.

“The one thing that I do dwell on is just how lovely it is that people from all these different ages and backgrounds—whether they’re muni golfers or country club golfers—they all seem to enjoy the work, and that makes me feel like I’m doing my job,” he says.

While Wybranski is humble about his talent as an artist, it’s obvious how absorbed he is in his work. When he zeroes in on subjects to sketch and paint, he enters into his own world. He speaks fondly of the sound the pencil makes as it begins to define the composition, the satisfying struggle of layering colors to suit the eye, even the distinct smell of his favorite paper as the first brushstrokes land.

And he’s still constantly pushing and challenging his chosen craft. To Wybranski, the creative process is “like grabbing sand.” There’s always something you might catch with your next work that you missed in the last one. And there’s always a new approach that can widen your range.

One of his biggest changes of late has been a shift away from the medium he’s been working in almost exclusively for decades.

“I love watercolor very much,” Wybranski says. “I love how natural it is. But watercolor as a medium is unforgiving. I just found that I really wasn’t enjoying it as much as I used to. That’s not what you want. So I began working with acrylic paint. I have none of the love affair with acrylic at all. That said, I’ve had a great time working with it. It’s loosened me up. I’ve made some paintings with the acrylic that are more vigorous and more dynamic and more bold. I’m happy to see those things in my work.”

He also continues to find joy in the days of scouting, the freedom and creativity that comes as he’s searching for the perfect perspective.

“This is the fun part,” he says. “Once I narrow in on it, there’s a ‘eureka’ moment when I really feel like I found the exact thing I’m looking for, but from that point forward, it’s much more execution and less of surprise and discovery.”

At the end of our visit, having spent nearly every free moment of the daylight hours covering as much of the property as humanly possible, Wybranski suddenly pauses mid-conversation.

Storm clouds are beginning to stack up in the distance, and the sound of the air horn to direct us off the course is imminent. Still, turning toward the tree line, he grabs his camera and takes off on a jog. Shimmying up a rock outcropping, he scans the horizon for one last panorama.

Was that the “eureka” moment? We’ll all know in a few months’ time.

“Once I narrow in on it, there’s a ‘eureka’ moment when I really feel like I found the exact thing I’m looking for, but from that point forward, it’s much more execution and less of surprise and discovery.”